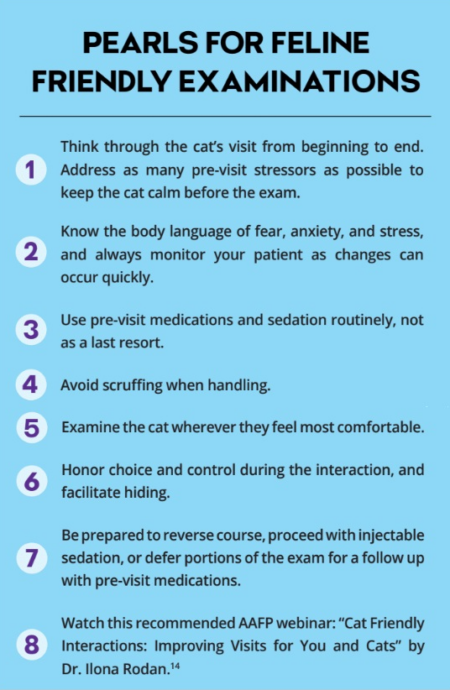

Reducing examination fear for cats starts well before the visit itself. By considering stressor stacking, the exam room environment, and cat friendly handling principles, youll be able to significantly reduce stress in your feline patients.

Veterinary care has traditionally prioritized the physical needs of the feline patient, giving little thought to their fear, anxiety, and stress during a clinic visit. However, with Low Stress Handling,1 AAFP Cat Friendly,2 and Fear Free3 initiatives, we now realize that by minimizing stress in our feline patients and advocating for their emotional needs, we can provide them with better care. In this article, we focus on ways to reduce feline stress associated with veterinary examinations.

Positive carrier training is a life skill for cats, and helps reduce stress associated with vet visits.

PRE-HANDLING CONSIDERATIONS

A cats visit doesnt start and end with the exam table. Stressor stacking, a phenomenon outlined in the 2022 AAFP/ISFM Cat Friendly Veterinary Environment Guidelines,4 describes how multiple stressors can accumulate and cause the cat to reach threshold faster. Always consider what the cat has experienced prior to the exam at home, during transport to the clinic, and within the clinic itself. Picturing a cat friendly visit from beginning to end, emailing clients information5 on how to decrease stress for vet visits, verifying that pre-visit medications are refilled and timed appropriately, and letting the client wait in the car so their cat can go straight into an exam room when ready, will help keep the patient as calm as possible.

Another vital aspect to reducing feline stress is considering the exam room itself. The AAFP/ISFM 5 Pillars of a Healthy Feline Environment4 should be on your mind whenever you handle a patient; in particular, pillars 1 (provide a safe place) and 5 (provide an environment that respects the cats sense of smell and other senses) come into play for the exam. Remove all traces of the previous pet with an unscented cleaner, especially olfactory triggers like urine, feces, or anal glands. Elevated surfaces and hiding options can make cats feel safer,4 so ask clients to place the carrier on the exam table when entering the room and drape a towel over the carrier before handling. Towels are one of the most important tools for the cat friendly exam, providing a warm, cozy surface and a means to cover the cat if they prefer to be hidden. In addition, stocking the exam room with a variety of treats,6 toys, and catnip will help serve as a distraction and hopefully change the emotional state of your patient.

The exam table surface should be comfortable and non-slip.4 If commercial exam table mats are out of your price range, yoga mats cut to the length of the table are a budget-friendly option for providing stability. Similarly, the scale used to weigh your patients during the exam should have a non-slip and non-tilt surface. This can be achieved with a simple shelf liner or cozy bathmat placed on the scale and tared prior to weighing the cat.

Finally, avoid using cat gloves, cat muzzles, E collars, cat burritos, and cat bags for the exam, due to their impact on feline welfare.7 If you find yourself using these routinely, consider changing your approach and goals, and rescheduling with pre-visit medications or injectable sedation.

FELINE HANDLING CONCEPTS

The 2022 AAFP/ ISFM Cat Friendly Veterinary Interaction Guidelines7 describe two types of emotional states we can see in cats: engaging (positive) emotions and protective (negative) emotions. Each of these states leads to behavioral responses we can observe during vet visits. Responses with underlying engaging emotions could include approaching a staff member for petting or treats, and exploring the room. Responses arising from protective emotions include avoidance, inhibited behavior, and distance-increasing, repelling behavior like hissing/swatting.

Reframing the emotional state of a cat in these terms Rather than using words like fractious or spicy is an important first step to understanding your patient. The Unlabel Me campaign8,9 by Applied Behavior Analyst, Dr. Susan Friedman, cautions against the use of labels and constructs for several reasons, including the inability of abstractions to cause behavior, and the danger of labels predisposing us to the use of aversive methods. For example: This cat is spicy, so I have to use cat gloves and a muzzle.

Another cat friendly principle you should keep in mind during any interaction is giving the patient as much control and choice7 as possible. We routinely move and handle pets in the clinic setting, while giving very little thought as to what they would prefer. Cats that choose to stay in their carriers get unceremoniously dumped and shaken out, while those that are relaxed in semi-lateral get scruffed and stretched into full lateral recumbency to access the medial saphenous. Supporting choice and control in every feline encounter has a remarkable effect on decreasing stress. Cooperative care10 takes those concepts to the next level, and through training, allows the pet to have agency in their own care. By indicating to the handler when they are ready to start and stop a procedure, such as an exam or blood draw, the pet has the greatest sense of choice and control, producing a calmer patient and safer handling.

patient as much control and choice7 as possible. We routinely move and handle pets in the clinic setting, while giving very little thought as to what they would prefer. Cats that choose to stay in their carriers get unceremoniously dumped and shaken out, while those that are relaxed in semi-lateral get scruffed and stretched into full lateral recumbency to access the medial saphenous. Supporting choice and control in every feline encounter has a remarkable effect on decreasing stress. Cooperative care10 takes those concepts to the next level, and through training, allows the pet to have agency in their own care. By indicating to the handler when they are ready to start and stop a procedure, such as an exam or blood draw, the pet has the greatest sense of choice and control, producing a calmer patient and safer handling.

If your cat chooses to stay in their carrier, avoid lifting or dumping them out as this will significantly increase stress and could lead to injury. Instead, take the top off the carrier and let them hide in a towel.

Additionally, I urge you to use minimal restraint when possible,7 and take the scruff-free pledge as outlined by International Cat Care.11 Not only does scruffing a cat take away control, but research has shown that cats placed into full-body restraint were 8.2 times more likely to struggle than cats that were minimally restrained.12 Additionally, cats that were scruffed were more likely to show negative behavioral and physiological responses than passively restrained cats.13 While not scruffing cats can seem like a paradigm shift for some, its one of the most profound steps you can take towards minimizing stress for your feline patient.

Providing every feline patient with choice and control will significantly decrease stress during their exam. This includes coaxing them to come out of their carrier on their own.

THE CAT FRIENDLY EXAM

Be ready to examine the cat wherever they feel most comfortable.7 You should also have a plan for what will occur during the visit, going from least stressful to most stressful procedures, which means in most cases youll want to perform your exam first. Ask your technician to avoid obtaining a weight or TPR before the exam, as these will often increase stress, particularly in a fearful cat whose safe place is the carrier. In addition, use the fewest number of people possible. When employing cat friendly principles and minimal restraint, only the doctor is often needed for the exam itself. As much as clients want to be involved with restraint, this should be discouraged for the sake of safety and liability. Instead, ask them to soothe their cat by talking to them or feeding them a treat, such as Churu, from a distance.

You can encourage your feline patient to emerge from their carrier by extending a soft hand as an invitation, placing a treat trail in front of the carrier, and engaging the client to help coax them out. Avoid eye contact and leaning over the cat. Asking the cat to come out on their own gives them choice and control. If they do come out, you can start your exam, but avoid the nose-to-tail approach many of us learned in vet school. Instead, similar to the visit plan, proceed in order of least stressful to most stressful areas of the body. Handling the face/head (especially the mouth and ears), abdomen, feet, and perianal/genital region are usually the most aversive to cats, so try to save these, as well as any potentially painful areas, until the end of the exam.

Using the Fear Free principle of Touch Gradient,3 the second you make contact with your patient, maintain that contact to avoid a startle response, and use a gliding motion. Starting in a neutral location such as the dorsal shoulders before gliding to another area helps the cat know where you are. Continually evaluate the cat for changes in body language while you gradually increase touch intensity. Be gentle with your pressure and aim for slow movements, taking care to avoid hyperextending, hyperflexing, and moving body parts in an unnatural direction. Many cats prefer to be petted/massaged in the area of their facial glands,7 and this type of touch rather than brisk petting can help decrease stress and arousal during the exam.

If the cat chooses to remain in the carrier, pulling or dumping them out is highly discouraged since removal from their safe place will increase stress and may lead to injuries. Instead, take the top off the carrier and use a towel to loosely cover the cat to allow for hiding. Many cats will burrow deeper into the towel to hide further. For fearful cats that choose to be covered, the entire visit can then be performed in the bottom of the carrier, including the exam, sample collection, and vaccination, saving face handling until the end. Tachypnea, tail position/movement, and growling will help alert you to increasing stress levels even when the cat is mostly hidden. Remaining fluid with your approach and reversing course will often allow increasing stress levels to de-escalate. Understand that you may not be able to safely examine every aspect of a cats body during a visit. Sending home a pre-visit anxiolytic such as gabapentin, administering analgesics, or progressing to injectable sedation can help facilitate a more thorough exam while caring for the cats emotional well-being.

Unfortunately, many cats are brought to the clinic in carriers that prevent cat friendly access for exams; e.g. when the screws are rusted shut. Client education on the best type of carrier to minimize stress for their next visit is an essential part of preparing for a cat friendly exam.

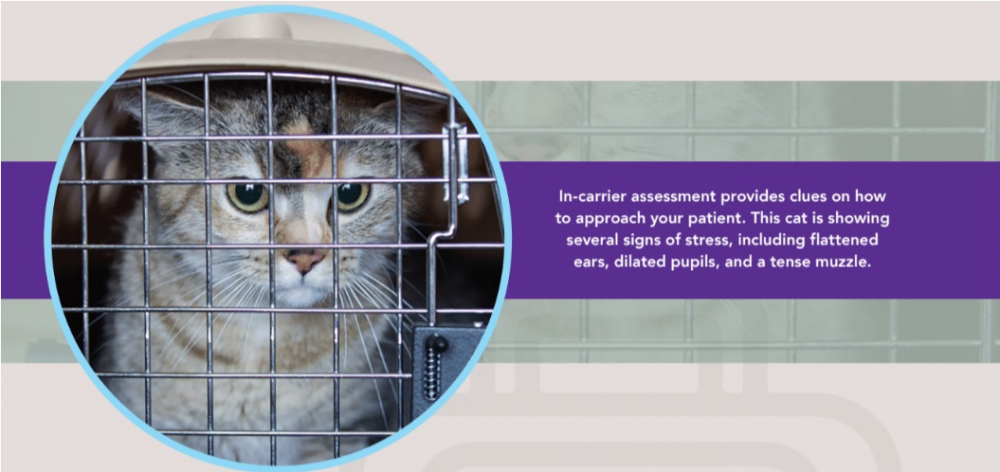

IN-CARRIER ASSESSMENT

Instead of jumping straight into the exam when you enter the room, take a few seconds to peek at your patient in their carrier and assess their body language. Its best to approach them from the side and avoid staring at them directly, as the latter can increase stress.7 As you become more familiar with the cats body language, youll be able to quickly judge from a distance how you might want to approach them. Always evaluate the cat as a whole, and as soon as you lay eyes on them, get into the habit of continually re-assessing their body language since stress levels can change quickly during a visit.

- Position in carrier. Is the cat towards the front of the carrier? This could mean the cat is approaching for petting, or feeling frustrated because theyre not positively carrier trained. Is the cat in the back of the carrier? Cats feeling fear, anxiety, and stress tend to stay in the back, and may even attempt to hide by facing the back of the carrier.

- General posture. Fearful cats may appear frozen and tense, with a hunched back and tail tucked tightly against their body.

- Pupil dilation. Calmer cats tend to have slit-shaped or almond-shaped pupils. When cats start to get more stressed, their pupils can become dilated.

- Ear position. Cats that are more relaxed typically have forward-facing ears. As stress levels increase, the ears start to flatten horizontally to the sides, and eventually may even be completely pinned back.

- Signs of extreme fear and stress. Hissing, growling, striking/swatting, urination, defecation, expressing anal glands, and open-mouthed breathing (when theyve been breathing normally at home) are clues your patient is already experiencing high levels of stress even prior to handling. For cats with these body language signs, its essential to initiate a conversation with the client about what youre seeing and their wants vs. needs before continuing. This is a Fear Free concept3 in which you explore what youd like to get done (wants) vs. what is truly medically necessary for that cat (needs) when deciding how to proceed with the cat. Much in general practice is a want, and in order to protect the emotional welfare of the cat and the safety of your staff, deferring the visit and rescheduling the patient to come back with gabapentin on board is usually a much better option. For true medical needs, you may have to proceed with in-carrier sedation depending on the patients body language and history. Animals are constantly learning, so continuing to handle a cat when theyre in a highly stressed state will make their next vet visit much more difficult.

Cats that are minimally restrained for their exam will struggle less, leading to a more thorough exam and lower stress levels for everyone involved.

SUMMARY

Reducing examination fear for cats starts well before the visit itself. By considering stressor stacking, the exam room environment, and cat friendly handling principles, youll help bring a compassionate approach to your patient, and invest in their emotional health for the future.