Which vaccinations you give your horse, and how often, depend on the individual animal, your location and other circumstances, including overall health.

As we’ve discussed in previous issues, only you and your veterinarian can determine your horse’s real risk of infection from the various diseases out there. It’s important to look at your horse’s potential exposure and health status before deciding on a protocol for vaccinations. This article will give you some of the background you need to make an informed decision.

West Nile virus

West Nile virus

West Nile virus (WNV) infection was first diagnosed in horses in 1999, and also produces serious disease in birds and people. Transmitted by mosquitoes and occasionally other bloodsucking insects, the virus is now considered to be endemic throughout North America.

Infected avian hosts serve as a natural reservoir for WNV, with crows being particularly susceptible. In endemic areas, public health surveillance includes notifying local authorities and testing dead crows or other birds for WNV.

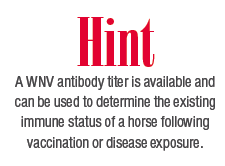

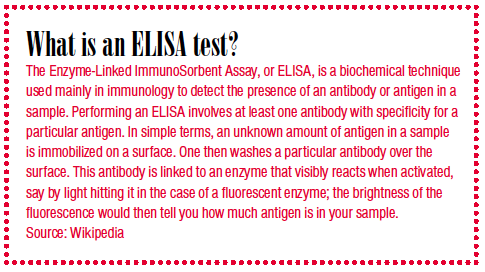

The incubation period in horses is three to 15 days, after which clinical signs of infection may appear. These include fever, stumbling or incoordination, depression or apprehension, stupor, behavioral changes, limb weakness, partial paralysis, droopy lip, teeth grinding, muscle twitching, tremors, difficulty rising, recumbence, convulsions, blindness, colic, intermittent lameness, and death. Because some of the clinical signs mirror other neurological disorders, you’ll need to get a differential diagnosis to determine if your horse does indeed have WNV. Your vet will make a diagnosis after measuring both capture antigen and antibody in ELISA tests (see page 42). The IgM-capture ELISA is considered the most reliable test for confirmation of recent exposure to WNV in a horse with clinical signs. Specific antibody persists four to six weeks after infection.

Horses with clinical signs have a mortality rate of about 33%. Up to 40% of those that survive the acute illness can exhibit residual effects such as gait and behavioral abnormalities for several months after. According to reports, more than 6,000 horses have been killed by this disease since 1999. The human death toll sits at about 1,000, while bird deaths number in the hundreds of thousands.

Choosing the safest WNV vaccinations

Both killed and modified live virus (MLV) vaccinations are available for WNV and both provide good protection. In fact, a recent study comparing killed, MLV, and live-chimera WNV vaccines found 100% protection with all three types following challenge with virulent WNV. It only makes sense, then, to ask your vet for the safer, inactivated, killed vaccine, especially since annual vaccination is strongly recommended due to the prevalence of this serious illness. You should also know that while vaccinations are a primary method of reducing the risk of infection from WNV, clinical disease is not fully prevented. However, while the efficacy rate of the vaccine is still debated, horses who have received vaccinations usually contract less severe disease if they become infected.

WNV dosage protocol

Two vaccinations are given initially three to six weeks apart, with boosters recommended every four to six months, depending on the exposure risk in a particular area. Annual vaccination is recommended in the spring before prime insect season. Whenever possible, mares should be vaccinated before breeding, although in highly endemic areas, veterinarians have also been vaccinating pregnant mares because of the risk of disease from infected mosquitoes (clearly, this is a risk-benefit issue). If booster vaccination is given to pregnant mares four to six weeks prior to foaling, the foal receives passive immunity from the colostrum that should last three to four months.

Foals delivered by vaccinated mares should not receive primary vaccinations before three to four months of age to avoid interference from the colostral immunity. Re-vaccination is recommended one month later, and then at one year of age, except in endemic areas where another dose is given at six months. Thus, in endemic areas, foals initially receive three doses of vaccine followed by a fourth dose at one year. Thereafter, boosters are given annually or more often in high-risk exposure settings.

Rabies virus

Rabies virus

Rabies infection occurs sporadically in horses as it does in all mammals, usually following a bite from an infected wild animal. Diagnosis is difficult in horses and must be done with immunofluorescent antibody testing.

Rabies vaccines are required because of the danger to humans. Because of safety issues, all are of the inactivated type. Both monovalent (single) and polyvalent combination vaccines containing rabies virus are available. Because of the documented increased risk of adverse reactions in dogs and cats when vaccines are given together rather than separately, and because rabies vaccine is known to elicit the strongest antigenic response, it is best to give single vaccines, at least two to three weeks apart.

This advice applies especially to rabies vaccine, which, in my opinion, should never be given together with another vaccine to any species. Furthermore, as rabies vaccines are known to provide protection against rabies for at least five or more years, annual revaccination of horses is not recommended unless mandated by law in your area. For more information on rabies vaccine, visit rabieschallengefund.org.

This advice applies especially to rabies vaccine, which, in my opinion, should never be given together with another vaccine to any species. Furthermore, as rabies vaccines are known to provide protection against rabies for at least five or more years, annual revaccination of horses is not recommended unless mandated by law in your area. For more information on rabies vaccine, visit rabieschallengefund.org.

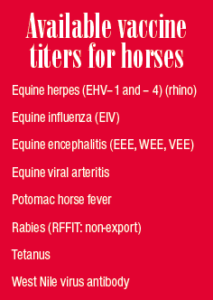

Rabies vaccine titers

An RFFIT rabies antibody titer is available for horses not destined for export. Serum samples are sent to Kansas State University, the federally recognized rabies serology laboratory. Testing takes two to three weeks to complete. Results come with a statement saying that protective rabies titers have not been determined for this species, although the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta have determined that a rabies antibody titer of 1:5 or greater (0.05 IU/mL) will protect humans from contracting the disease. This titer level has been extrapolated to other mammals to be protective.

Equine arteritis virus

Equine arteritis virus

Equine arteritis virus (EAV) produces infection and abortion in mares and a carrier state in infected stallions.

Both MLV and inactivated EAV vaccines are available. Since the vaccine can induce a mild adverse reaction, I would discourage vaccinating pregnant mares and instead vaccinate at least three weeks before breeding, if you choose to do so. These vaccines do not protect horses against infection from the virus but provide a variable degree of immunity to the clinical disease.

Vaccine titers can be measured against EAV but are of questionable value in predicting protection against infection and disease.

Other equine viral diseases

Equine infectious anemia is caused by a retrovirus but no vaccines are available. Equine rotavirus infection is a major cause of diarrhea and foals throughout the world. An inactivated bovine vaccine given to pregnant mares has been shown to produce antibodies in the milk to passively protect suckling foals; however, vaccination of pregnant mares should be viewed with caution.

Potomac horse fever

Also called equine monocytic ehrlichiosis, Potomac horse fever is caused by the rickettsial organism, Ehrlichia ristici (recently renamed Neorickettsia risti). It produces an acute enterocolitis syndrome with mild colic, fever, and diarrhea in horses of all ages, as well as abortion in pregnant mares. Tetracyclines are the conventional treatment of choice, along with anti-inflammatory agents if needed. Inactivated vaccines are available that reduce the clinical signs but do not provide full protection.

Equine granulocytic ehrlichiosis

Equine granulocytic ehrlichiosis

This disease is caused by infectio with Ehrlichia equi (recently renamed Anaplasma phagocytophila). It is a non-contagious infectious seasonal disease transmitted by ticks and seen primarily in northern California, although it has more recently spread to other parts of North America. Clinical signs are often mild, with fever only, or fever and depression, mild limb edema, and ataxia. There may also be partial loss of appetite, depression, reluctance to move, limb edema, small pinpoint hemorrhages, and jaundice. Tetracyclines are the conventional treatment of choice. There are no vaccinations available.

Other equine bacterial diseases

Lyme disease in horses and other species is caused by the spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, and is transmitted by infected ticks. Strangles, due to Streptococcus equi infection, is an acute contagious respiratory disease of young horses. Adjuvanted killed vaccinations are available but these may cause both local and generalized adverse reactions. None of these vaccinations are completely effective in preventing the disease, likely because they fail to produce mucosal surface immunity in the upper respiratory tract. I do not recommend them at this time.

Contagious equine metritis (CEM)

This is a highly contagious venereal infection of horses causing short-term infertility. Stallions do not develop clinical signs of the disease but can harbor the infection and transmit it during breeding. There is no vaccine for CEM.

Again, which vaccinations you give your horse, and how often, depend on the individual animal, your location and other circumstances, including overall health and whether or not she’s pregnant.

Work with a vet who is open to creating the safest and healthiest protocol for your own horse’s needs.

References

AEP. Guidelines for vaccination of horses, 2001; West Nile virus vaccination. Supplement, 2005. Desmettre P. “Diagnoses and prevention of equine infectious diseases: present status, potential, and challenges for the future”. Adv Vet Med 41:359-375, 1999. Seino K.K., Long M.T., Gibbs E.P., et al. “Investigation into the comparative efficacy of three West Nile Virus vaccines in experimentally induced West Nile Virus clinical disease in horses”. AAEP Proceed 52:233-234, 2006. Rosenthal M. “Practitioners, concerned about safety, embracing new vaccine recommendations”. Product Forum & Market News, Spring 2007 Tizard I, Ni Y. “Use of serologic testing to assess immune status of companion animals”. J Am Vet Med Assoc 213: 54-60, 1998.