What exactly is pasture-associated laminitis, and why does it occur? This past spring, as I drove by emerald green pastures on my way to work, I couldn’t help but recall the words my father told me as a child. He always said my pony couldn’t be turned out with the other horses in the spring because the grass was too “lush” and she might get sick. I was always upset because Misty couldn’t go out and graze on these beautiful days with her friends in upstate New York. She was a portly little Welsh pony who got fat on air, and in addition to limiting her spring days in the lush pasture, my dad also kept her grain to a minimum. It seemed so unfair at the time.

As fate would have it, though, I found out that my dad’s warning probably saved my pony from many health problems. Over lunch one day at Virgina Tech, where I was a graduate student, my advisor Dr. David Kronfeld asked if I would be interested in helping with a study on pasture-associated laminitis in Welsh ponies. Naturally, I agreed.

In the ponies we studied, a pre-laminitic metabolic syndrome (PLMS) that included insulin resistance was identified. We found that the pasture-associated laminitis occurred in April and May, when pasture nonstructural carbohydrate (NSC) content was at its highest. These findings led to my PhD research further examining carbohydrate profiles in forages, and the digestive and metabolic response in grazing horses. Our objective, of course, was to find a way to avoid pasture-associated laminitis, the condition my father was referring to when he said Misty might get “sick”. The NSC content was what made the grass “lush”.

Although laminitis has many causes, nearly half of cases in the U.S. and Canada are pasture-associated laminitis cases, particularly in the spring.

Hopefully by reading through the results of this research, you’ll gain some insight into how to keep your horse free from this condition.

How high NSC can trigger pasture-associated laminitis

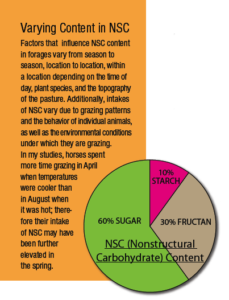

Sugars (glucose, sucrose, and fructose) are the readily available carbohydrates in plants. Fructans are the primary storage carbohydrate in cool season grasses such as tall fescue, orchard grass and perennial ryegrass. Starches are the primary storage carbohydrate in legumes like clover and alfalfa and warm season grasses such as Bermuda grass. Sugars and starches are digested primarily in the small intestine of the horse, but if a horse eats too much, they are rapidly fermented in the hindgut. Horses cannot digest fructans, so they too undergo rapid fermentation by hindgut microbes.

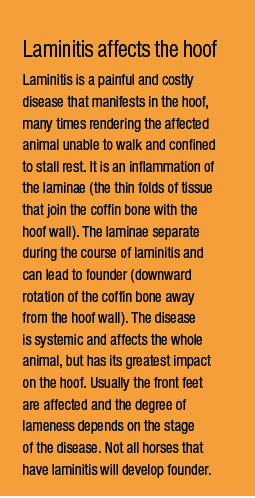

Rapid fermentation of NSC in the hindgut causes an increase in lactic acid production and a decrease in cecal fluid pH. The bacteria in the cecum then release toxins (endotoxins, exotoxins or certain amines) that enter the bloodstream and trigger laminitis by reducing blood flow, oxygen and glucose in connective tissue within the laminae.

Laminitis is also associated with insulin resistance. The uptake of circulating glucose by hoof tissue cells normally potentiated via insulin is reduced, leading to a poor glucose supply. Insulin resistance is often seen in very fat horses and ponies, and may be exacerbated by high intakes of sugars and/or starch.

What the research reveals

What the research reveals

The research focuses on identifying animals predisposed to developing laminitis, and on avoiding dietary risk factors. Since many cases of laminitis are associated with pasture consumption, one way to avoid the disease is to restrict access to pasture when NSC content is high, and provide alternative feeds known to be lower in NSC.

My PhD research consisted of a series of 36-hour studies that took place in April, May, August, and October 2005, and January 2006 at Virginia Tech’s M.A.R.E. Center. The studies evaluated pasture NSC content, and the digestive and metabolic variables in grazing horses compared to horses in stalls who were fed hay only. Pasture forage samples were collected every hour and analyzed for NSC. We used a new enzymatic technique to measure sugars, starch, and fructan individually, and NSC was calculated as the sum of these constituents. Every hour, corresponding blood samples were collected from the horses and analyzed for insulin and glucose (to evaluate carbohydrate metabolism and identify insulin resistance).

Fecal samples were collected every four hours and analyzed for pH, lactate, and volatile fatty acid (VFA) concentrations (to evaluate digestive variables and potential rapid fermentation).

The results of our study indicated that forage NSC content was influenced by time of day, season, and environmental conditions. Specifically:

The results of our study indicated that forage NSC content was influenced by time of day, season, and environmental conditions. Specifically:

• Forage NSC content was highest in April and ranged from 16% to 25 % (dry matter) throughout the 36 hours. In the other months, NSC never exceeded 16% dry matter.

• Overall, sugar made up 60% of the NSC content, fructan 30% and starch 10%.

• Circadian (24 hour) patterns in forage NSC were evident in April, May, and August, with the most distinct pattern found in April. The lowest content was found in the early morning hours before sunrise (4:30 am), with increases observed throughout the day, reaching a peak at 4:30 pm. The circadian fluctuation was attributed to environmental conditions, which included cold night temperatures followed by bright sunny days and low humidity. In October, the low NSC content was attributed to mild temperatures, low sunlight, and rain.

The studies also indicated that pasture NSC altered digestion and metabolism in the grazing horses.

• In April, grazing horses had higher insulin concentrations than horses fed hay. Insulin concentrations in grazing horses that month were more than two times higher than in May, and more than four times higher than in August, October and January.

• In April, some individual horses had very high insulin levels. They appeared to be more sensitive to daily increases in NSC than horses with lower insulin concentrations.

• Fecal pH and volatile fatty acids (end products of hindgut fermentation) were also highest in April, possibly indicating digestive upset due to rapid fermentation.

Are NSC levels and laminitis linked?

My studies identified a potential link between forage NSC content and laminitis. Alterations in carbohydrate metabolism and digestion may increase the risk of laminitis through the exacerbation of insulin resistance and rapid fermentation in the hindgut. A notable observation was the low fructan and relatively high simple sugar content. Simple sugars, rather than or in addition to fructans, may be important in the pathogenesis of metabolic and digestive disorders such as laminitis in grazing horses.

Once pasture-associated laminitis occurs it is extremely difficult to treat, and horses often never recover fully. If you suspect your horse or pony is prone to laminitis, avoid grazing pasture when NSC content is high, and provide hay forage and a feed that are both low in NSC.

Once pasture-associated laminitis occurs it is extremely difficult to treat, and horses often never recover fully. If you suspect your horse or pony is prone to laminitis, avoid grazing pasture when NSC content is high, and provide hay forage and a feed that are both low in NSC.

When having your forages or feeds tested by a laboratory, it is important to understand what they are measuring because analytical techniques differ between labs. Even if you know what your NSC content is, there are currently no designated cut-off points for “safe” levels in forages and feeds, so making specific recommendations is difficult.

My childhood pony Misty is still living in New York and has never encountered pasture-associated laminitis (or any form of laminitis, for that matter) in her long life. My father may not have known all the scientific reasons for avoiding lush pastures, but there was definitely something in his practical horsemanship! So if you live in an area where spring brings greener pastures, you may be wise to reevaluate your horse’s grazing habits… and potentially keep pasture-associated laminitis far, far afield.

Bridgett McIntosh recently received her PhD from Virginia Tech, where her research focus was on carbohydrate profiles in feeds and forages and the avoidance of equine laminitis. She is currently an Equine Specialist for Blue Seal Feeds, Inc., working directly with horse owners and sales managers to optimize equine nutrition and the application of feeding management for horses. She is an avid rider and enjoys competing on the hunter/ jumper circuit, as well as foxhunting.