Addressing the nutritional and energy needs, as well as managing heat during exercise, are the foundations for a healthy dog.

Building foundations for a healthy dog means combining several factors such as fitness, nutrition, task training, and musculoskeletal maintenance (including the use of integrative therapies). This article will focus on the foundations of energy and nutritional needs to support exercise and structure, as well as the management of heat during exercise. Applied (w)holistically and appropriately, these approaches can help keep an active canine healthy and happy throughout his life and create the foundations for a healthy dog.

The active dog’s unique needs

Over the 35,0001 years since humans domesticated them, dogs have been selectively bred for certain characteristics. These characteristics enabled them to perform desired jobs, such as hunting, herding, pulling, protection, detection, and active companionship. More recently, humans have concentrated the dog’s pack-driven predator drives of prey detection, stalking, hunting and killing into specific looks, athletic abilities, and on-demand behaviors.

The unique needs of the modern active dog are starting to be addressed by the veterinary medical world. In 2010, the US saw the introduction of the first boarded specialty focused on active canine sports medicine, as well as the rehabilitation approaches needed to help dogs heal from various injuries. The scientific and practical knowledge aimed at improving the quality of work and life for active dogs has been growing by leaps and bounds ever since. As people become more educated about their dogs through clubs and readily available educational sources, it is important for veterinarians to stay as up-to-date as their clients on the newest research regarding active canine energy, fitness, exercise and musculoskeletal health needs.

A quick note about lameness

An article dealing with soft tissue injuries alone would fill this journal, and the goal here is to present new information on other less well-known but foundational topics. Therefore, readers are referred to the resources listed at the end of this article for additional information on addressing lameness and gait abnormalities in active dogs. The author would just like to strongly emphasize that one does not need to refer everything to a surgeon in order to successfully diagnose and treat lameness issues in active dogs. Not every hind leg lameness is a cranial cruciate strain, and not every front leg lameness can be traced to the shoulder.

Simple strains and sprians can affect dog gait

There are plenty of other joints, ligaments, muscles and tendons that a high-drive agility dog can injure by slipping on wet grass. Remember that any tissue or structure, anywhere, no matter how small, can be injured to the point of affecting gait. It is the author’s experience from over 25 years of working on active dogs that the majority of presented injuries are simple strains and sprains. All a practitioner needs to bring to the table of the lameness exam is to:

- Review one’s functional anatomy knowledge (one does need to know which muscles, tendons and ligaments are where and what they do)

- Watch the dog move on various footings to evaluate biomechanical function

- Thoroughly examine all limbs using static palpation and focusing on texture, heat and sensitivity

- Carefully examine the range of motion of each joint

- Be open to the possibility that any palpated abnormality could be causing the soreness.

From the results of a good physical exam, areas of interest can be identified for additional therapy or imaging. The more time one spends on identifying any and all possible lesions, the less time is lost going down therapy dead-ends, and the faster dog can return to health.

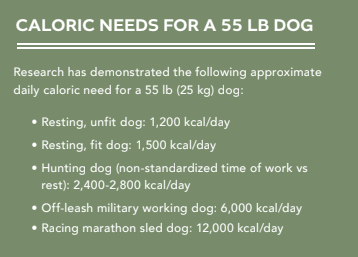

Energy and nutrition

It almost goes without saying that active and working dogs have greater energy needs than the average pet dog (see sidebar on page xx). Typically, sports medicine researchers thought dogs compared equally to humans and horses in how their muscles (and to a more minor degree, tendons and ligaments) prioritize energy sourcing during exercise: glucose first, then fats, and finally protein (amino acids). Nerve cells, critical not only for muscle movement, but also to nose function, can only use glucose (carbohydrates). It turns out, however, that the dog creates energy a bit differently than other species.

When exercise begins, the first few seconds of work are sustained by glycogen (a form of sugar) stored in the muscle cell itself. Cellular glycogen is much like having cash in one’s pocket; it provides just enough oomph to get things up and rolling until the real money – glucose circulating in the blood – can get to the cells to keep the work going. Once cellular glycogen and circulating glucose have been consumed, humans and horses typically turn to making sugar from fats for more sustained energy. Dogs, it turns out, do something very different. Instead of going to fat for more energy, the dog’s body will deaminate all the various proteins in the liver as the next step to making energy for cells. Therefore, active dogs will consume and have a turnover of protein to sustain the energy of activity.2-5

Consequences of protein turnover

Consequences of protein turnover

This protein turnover as a preferred energy source can have two unique consequences not seen in human and equine athletes.

- It will lead to greater protein breakdown and consumption, potentially removing proteins needed for musculoskeletal structure and leading to a weakening of structures such as muscle fibers, tendons, ligament, fascia, and joint capsules. Since a fit dog has more protein than fat structures, the fit dog will need to replace more consumed proteins than an unfit one, meaning that the former needs to be on a higher protein diet than the sedentary one.

- Because of the need to clear out nitrogenous wastes left over from increased protein metabolism, there is a greater demand for fluid to wash out the increased nitrogen. This plays a role clinically when interpreting both chemistries and urinalyses as exercising dogs could have higher BUN & creatinine values – they aren’t in kidney failure, they are just excreting the products of metabolism.

Glucose transporters

Another interesting thing the dog’s body does differently when it comes to energy involves insulin-independent glucose transporters. Glucose transporters sit in a cell membrane and control how glucose enters the cell. Normally, they are insulin-dependent, opening up only when insulin starts to circulate in the blood. However, all species have recently been shown to have temporary glucose transporters that are insulin-independent, which means they are open all the time. These transporters move to the cell membrane in response to signaling from contracting myocytes. Interestingly, dogs have four times more of these transporters than humans or horses.6-8 Once muscle contraction ceases, the body starts to remove those transporters off the cell membrane – within 30 to 40 minutes, they are back into cellular storage and insulin is once again needed to get glucose into the cell.

Overall then, active dogs need diets higher in protein and carbohydrates than previously thought.

Feeding the dog’s nose

Now, what about the nose? Dogs doing scentwork (SAR, detection, barn hunt, tracking, nosework) have additional special energy demands on top of the muscular ones. Nearly a third of the total mass of the dog’s brain is dedicated to scent detection and discrimination – 40% more than in humans. In a working, scent-based dog, not only do the neurons of movement have to be fed but so do those responsible for processing scent. When the brain and sense nerve cells run out of sugar and energy, dogs shut down and stop working mentally as well as physically.

In terms of feeding the nose, studies have shown that coconut oil supplementation decreases scent discrimination in hunting dogs, but corn oil and animal proteins in the diet increased it.9-11 The research cited using corn oil for PUFA supplementation; however, due to higher levels of pro-inflammatory Omega-6 fatty acids, as well as the presence of petroleum distillate and pesticide residues in US corn oil, this is not an oil I recommend for dogs. Instead, I recommend flax oil or egg yolks, combined with animal protein, for scent-based working and active dogs.

Exercise recovery in active dogs

Because of the dog’s use of insulin-independent transporters during exercise, a technique known as “glycogen post-loading” can be used for exercise recovery in active dogs. Despite being originally recommended for sled dogs, it’s very applicable to all working dogs. After exercise is finished, the body is desperate to restock that initially consumed glycogen, so for a short period of time (approximately 30 to 45 minutes in humans and sprint sled dogs) the body will use those insulin-independent glucose transporters to more easily move glucose into the cell without the insulin needed to open the cell gate.

Studies have shown that muscle glycogen can be rapidly restored with quicker muscle and nerve recovery if dogs are fed an easily digested carbohydrate meal within 40 minutes of exercise – and with no insulin spikes.12,13 To “glycogen post-load”, I recommend a couple of honey packets, electrolyte drinks, or ice cubes made from powdered Gatorade® (with no artificial sweeteners) or the more organic Skratch® (make according to label directions then dilute again in half), or yogurt/berry/banana smoothies. You can electrolytes with bone broth to improve palatability. If given after the 30 to 45 minute time frame, the sugar creates high blood glycemia (and a subsequent insulin spike) as well as more fat and inflammation. Using an electrolyte also helps recover the electrolytes, especially potassium, lost through panting.

Diets for active dogs

In helping clients put together diets for their active dogs, keep in mind both protein and carbohydrate levels. And remember that not all carbohydrates are the same. The point of having dietary carbs in a working dog’s diet is so they are readily digested and quickly available. Unfortunately, it’s the rare dog food manufacturer that actually puts carb levels on the package’s Guaranteed Analysis (GA).

Carbohydrate determination

To determine how many carbohydrates are in any particular food, you can check to see if it’s on the manufacturer’s website, go to an evaluation website such as www.dogfoodadvisor.com, or calculate backwards from the GA. To do the latter (which is a rough guestimate), start with 100%, subtract the protein, fat and fiber listed on the package’s GA, then subtract 20% from that for water, vitamins and minerals. What is left is a rough approximation of the carbohydrate quantity (but not quality).

I like to have mid-distance or effort working dogs such as hunting, tracking, herding and SAR canines on about a 20% to 30% carb diet while they are working. You can add glucose to a base kibble or raw food diet by adding maltodextrin, honey, Karo Syrup, high fructose corn syrup, other high glucose syrups or fruit. Watch quality and sourcing to make sure they are clean and free of pesticides/herbicides.

Protein determination

In terms of protein, a study done in 1999 on sled dogs showed that if dietary protein dropped below 18%, dogs started experiencing more injuries.14 The magic number seems to be between 30% to 35% protein in the GA. More than 35% was considered too high, causing additional water and oxidative stress on the body, although research is starting to find it depends on the type of protein. So that means an active dog should probably be fed a diet that is about 30% to 32% protein. If the protein is too low, conversely, the dog will start consuming his own proteins, leading to structural weakness. Sled dog diets of blended raw and commercial foods are also applicable to everyday active dogs.

The issue of hyperthermia

Between the human, horse and dog, the dog is most efficient in terms of energy production and usage. But surprisingly, the dog is also least efficient at clearing excess heat wastage caused by exercise away from his muscles, core and brain. Humans and horses clear heat through the capillary heat exchangers associated with sweat glands in their skin. Dogs cannot. But as long as blood supply moving to cooler areas can keep up with muscle activity, the heat generated from exercise is within normal tolerance.

Dogs are homeotherms

A dog’s inability to sweat except on his paw pads means that heat can build up quickly and dangerously in the muscles of working canines. Dogs are considered homeotherms, which means they have a limited tolerance to any deviation from their normal temperature; an average dog can only tolerate about a 3.5°F to 4°F increase in body temperature before things can become dicey.15,16.A trotting dog only has about eight minutes of metabolic heat that can be absorbed before cooling systems need to kick in; a galloping dog has about two minutes. This is because the dog only has two ways to cool himself – blood flow to the mouth (the major way) and pad sweating.

How dogs cool off

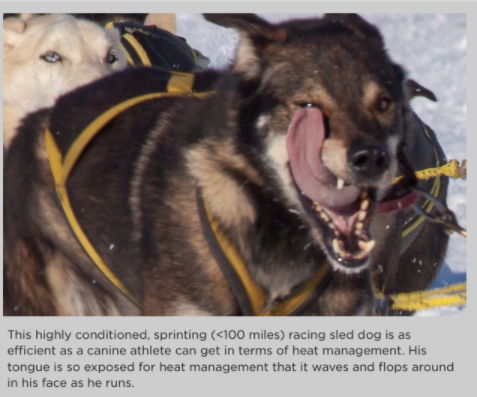

Dogs rely on heat exchange via panting to stay cool. As panting moves air through the respiratory system, the blood in the lungs (and around the head) is cools through the evaporation of fluid over the mouth’s mucous membranes and the surface area of the tongue; this in turn facilitates rapid heat exchange back into the lung’s blood supply. Cardiovascular fitness (stroke volume) is the biggest determinant of how well a working dog can cool off; therefore, a fit and conditioned dog can cool off better than one that is unfit. Evaporation of one liter of fluid through panting will cause a loss of about 540 kcal of heat. But it can also lead to significant dehydration, which can in turn drop blood flow and increase hyperthermia. Proper hydration is one of the best ways to keep a dog cool.

Signs of hyperthermia

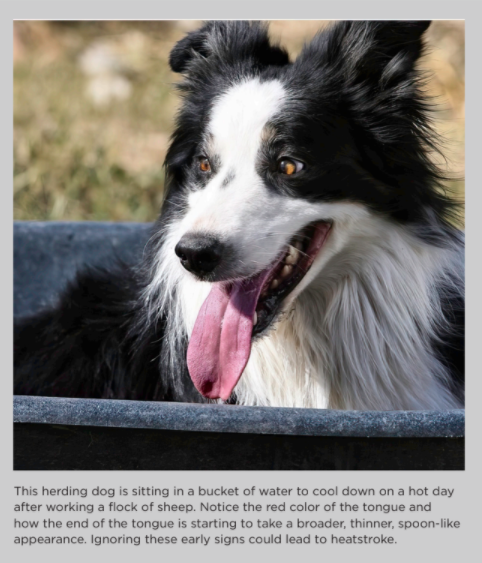

The hotter a dog’s core (or brain) thermostat gets, the more of the tongue’s surface area will start to show from the mouth, and the wider the dog’s mouth will become as he pants. Note: trained fit dogs that have a higher heat tolerance will start panting earlier than unfit dogs. As the dog goes into heat stroke, the mouth opens wider and the tip of the tongue widens into a spoon-like bowl shape. That tongue shape means the dog is struggling to cool off and approaching a critical hyperthermic threshold.17,18 If this happens, take immediate steps to cool the dog down!

Treating hyperthermia

- The best approach is to not allow the dog to get into distress to begin with. And don’t assume that just because it’s winter, the dog will not overheat. A sled dog trotting in cold temperatures can still end up with an internal body temp at a steady 103°F to 107°F.

2. If a dog’s tongue is becoming longer and wider, and the dog is acting like he thinks he’s hot, stop the exercise immediately and apply cooling interventions.

3. If a dog enters a hyperthermic crisis, it is critical to cool him down any way possible – period. If that means dunking his head or whole body in cold water, or packing the dog in snow, then so be it. Life-threatening post-hyperthermia medical events are not usually related to hypothermia from cooling interventions. They are related to the hyperthermia that preceded it, so getting body temperature down is imperative.

Summary

The foundations for a healthy dog encompass a high protein, moderate carbohydrate diet, and proper hydration at all times. Glycogen post-loading with electrolyte mixtures, fruit and honey can be beneficial to the dog’s quick recovery from exercise. Hyperthermia is a real danger in working and active dogs. It manifests as changes in panting behavior and tongue appearance as the dog attempts to cool his respiratory system (and brain) down. If the warning signs of hyperthermia appear (see sidebar on page xx), stop all exercise immediately and implement cooling interventions.

_________________________________________________________

References

1Skoglund P, Ersmark E, Palkopoulou E, Dalén L. Ancient wolf genome reveals an early divergence of domestic dog ancestors and admixture into high-latitude breeds. Curr Biol. 2015;25(11):1515-1519. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.019.

2Miller BF, Ehrlicher SE, Drake JC, et al. Assessment of protein synthesis in highly aerobic canine species at the onset and during exercise training. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2015;118(7):811-817. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00982.2014.

3Pratt-Phillips SEO R, Geor R, Zirkle A, Moore A, Harkins C, Davis MS. Effect of reduced protein intake on endurance performance and water turnover during low intensity long duration exercise in Alaskan sled dogs. <span style=”font-weight: 400;”>Comparative Exercise Physiology 2018;14:7.

4Tosi I, Art T, Boemer F, Votion DM, Davis MS. Acylcarnitine profile in Alaskan sled dogs during submaximal multiday exercise points out metabolic flexibility and liver role in energy metabolism. <span style=”font-weight: 400;”>PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0256009. Published 2021 Aug 12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0256009.

5Wasserman DH, Cherrington AD. Hepatic fuel metabolism during muscular work: role and regulation. Am J Physiol. 1991;260(6 Pt 1):E811-E824. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.6.E811.

6Davis MS. Glucocentric Metabolism in Ultra-Endurance Sled Dogs. Integr Comp Biol. 2021;61(1):103-109. doi:10.1093/icb/icab026.

7Barrett MR, Scott Davis M. Conditioning-induced expression of novel glucose transporters in canine skeletal muscle homogenate. PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0285424. Published 2023 May 3. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0285424.

8Barrett MR, Scott Davis M. Conditioning-induced expression of novel glucose transporters in canine skeletal muscle homogenate. PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0285424. Published 2023 May 3. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0285424.

9Altom EK, Davenport GM, Myers LJ, Cummins KA. Effect of dietary fat source and exercise on odorant-detecting ability of canine athletes. Res Vet Sci. 2003;75(2):149-155. doi:10.1016/s0034-5288(03)00071-7.

10Angle CT, Wakshlag JJ, Gillette RL, et al. The effects of exercise and diet on olfactory capability in detection dogs. J Nutr Sci. 2014;3:e44. Published 2014 Oct 13. doi:10.1017/jns.2014.35.

11Davenport GM, Kelley RL, Altom EK, Lepine AJ. Effect of diet on hunting performance of English pointers. Vet Ther. 2001;2(1):10-23.

12</span>Zanghi BM, Middleton RP, Reynolds AJ. Effects of postexercise feeding of a supplemental carbohydrate and protein bar with or without astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis to exercise-conditioned dogs. <span style=”font-weight: 400;”>Am J Vet Res. 2015;76(4):338-350. doi:10.2460/ajvr.76.4.338.

13Schnurr TM, Reynolds AJ, Komac AM, Duffy LK, Dunlap KL. The effect of acute exercise on GLUT4 levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of sled dogs. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2015;2:45-49. doi:10.1016/j.bbrep.2015.05.002.

14Reynolds AJ, Reinhart GA, Carey DP, Simmerman DA, Frank DA, Kallfelz FA. Effect of protein intake during training on biochemical and performance variables in sled dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1999;60(7):789-795.

15Hemmelgarn C, Gannon K. Heatstroke: clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Compend Contin Educ Vet. 2013;35(7):E3.

16Hemmelgarn C, Gannon K. Heatstroke: thermoregulation, pathophysiology, and predisposing factors. Compend Contin Educ Vet. 2013;35(7):E4.

17Otto CM, Hare E, Nord JL, et al. Evaluation of Three Hydration Strategies in Detection Dogs Working in a Hot Environment. Front Vet Sci. 2017;4:174. Published 2017 Oct 26. doi:10.3389/fvets.2017.00174.

18Stephens-Brown L, Davis M. Water requirements of canine athletes during multi-day exercise. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32(3):1149–1154. doi:10.1111/jvim.1509.

For further information

Henneman K. Recognizing soft tissue injuries in the dog from an integrative perspective, Parts 1 & 2, IVC Journal, Fall 2018, Winter 2018/19.

Zink C, Van Dyke JB (eds). Canine Sports Medicine & Rehabilitation, 2nd edition (note that the 3d edition is due out shortly), John Wiley & Sons: 2018.

Fischer MS, Lilje KE. Dogs in Motion, Pet Book Publishing Company, Ltd: 2016.

Von Pfeil D, Griffitts C (eds). Musher and Veterinary Handbook, 4th Ed (in publication), ISDVMA: 2024 (older editions are still available through the International Sled Dog Veterinary Medical Assoc, www.isdvma.org).

<span style=”font-weight: 400;”>Elliott RP. Dog Steps, ref=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S3YkRX4M088&t=5s”>www.youtube.com/watch?v=S3YkRX4M088&t=5s (still one of the best videos ever made about dog movement).