Hyperthermic therapy is the new kid on the block when it comes to treating cancer, but it’s showing promise for some tumor types.

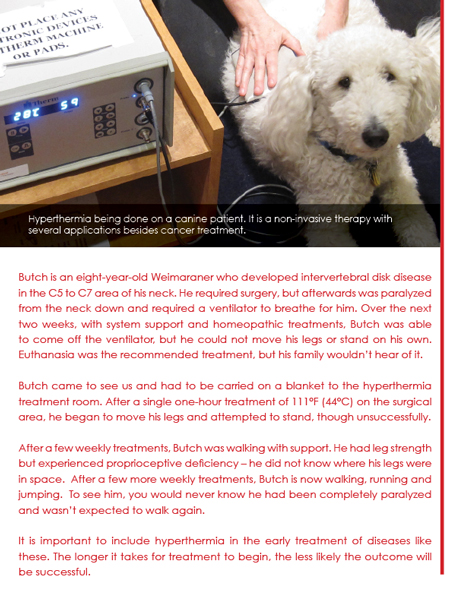

One recent addition to the integrative treatment of some cancers is hyperthermia, or hyperthermic therapy. It involves heating the body, or an area of the body, above its normal physiological temperature. Hyperthermia isn’t just about superficially heating tissues with hot packs, however. It’s more akin to the body’s own physiological response of creating a fever during illness. In other words, hyperthermic units use a mat or pad to create a local fever, which deeply penetrates into the tissues.

How does it work?

How does it work?

Hyperthermia stimulates the body’s repair processes by dilating blood vessels to specific areas of the body. This allows medication to get into these areas quickly so inflammation is reduced and tissue toxins are removed. Tissue elasticity is also maintained, resulting in reduced sclerosis or scarring.

Hyperthermic therapy can be used for treating some cancerous tumors as well as some bacterial infections, and many musculoskeletal and neurological disorders (see sidebar).

Cancer is a collection of disorganized blood vessels and cells, which means a tumor mass does not cool down as quickly as healthy tissues after a hyperthermia treatment. Heating the tissue creates heat-shock proteins that help upregulate apoptosis (cell death) and modulate or reduce the drug resistance of cancer cells to chemotherapy, so these latter treatments may be given at lower doses.

Mild hyperthermia can increase oxygen delivery to a tumor, but the heat used in treatment has been shown to damage the tumor’s blood supply, eventually lowering the oxygen available to it. Lowered oxygen lowers the tissue pH, and this increase in acidity leads to added ischemia and cell death.

Hyperthermia is generated in two ways: electromagnetic or ultrasonic radiation. The cancer area is heated to an internal temperature of 104°F (40°C) to 115°F (46°C) after chemoperfusion of the tissue. Magnetism can also play a role – in theory, when using a metallic-based chemotherapy agent and a magnetic hyperthermic unit, all the metal in the chemotherapy medication will be pulled toward the magnet, damaging the cancerous tissue so it can be more effectively killed by the chemical agent or radiation.

Still being studied

Hyperthermia is still under investigation for cancer treatment and is not considered a stand-alone therapy, but it’s showing promise. We have admittedly not had great success with it to date, but our case numbers have not been high. For example, a dog named Fred was diagnosed with a nasal mast cell tumor that regrew after surgical removal. The tumor was infiltrated with Carboplatin while he was under general anesthesia, then heated for an hour to bring the internal temperature of the tumor up to 113°F (45°C). Initially, we saw some of the cancer tissue isolate, scab and fall off, shrinking the tumor. However, it spread to the other side of the nose, and subsequent treatments did not seem to stop it.

On the other side of the coin, practitioners in Europe and some in the US have had good results using hyperthermia on difficult tumors such as feline fibrosarcoma. Either way, this therapy and its applications for cancer are definitely worth further study.