How can horses support their own weight, let alone ours? Discover the important role that biomechanics play in the rider/horse relationship.

For millennia, horses have worked as our partners in the advancement of civilization. Until the rise of the internal combustion engine, our ability to partner with horses was necessary for survival. A successful partnership brought better crops, carried you long distances, and even brought you home from war. This symbiosis has its roots in the sharing of intention between horse and human, to develop and maintain a cooperative and beneficial relationship. And biomechanics is what makes this relationship possible in the first place.

Horse and rider interaction

A human riding a horse is the quintessential demonstration of this relationship, and at its best, expresses a profound joining across species. But we don’t often stop to think about the basis of this connection.

Let’s examine the components of horse and rider interaction. The horse needs to physically carry the rider, the rider needs to communicate her intention, and both need to cooperatively accomplish the task. All this, while maintaining continuous feedback, moment by moment, and reacting to changing conditions that might require new choices. While the complexity and difficulty of each activity varies based on the physicality, experience and skill of each team member, all three elements are constant in ridden work.

Weight bearing, balance and the equine spine

The physical act of carrying a rider is both simple and enormously challenging for a horse. Horses are one of the largest and fastest land animals. Carrying their own weight requires significant mechanical and physiologic adaptations. Equine spines, as with all quadrupeds, are positioned horizontally, like a beam, not vertically like our own spinal “columns”. Four legs and a horizontal spine make it easier for horses to balance their bodies; foals don’t need two years to learn how to walk, like human babies do.

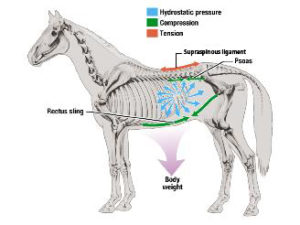

However, gravity would cause a horse’s trunk to sag down in the middle without special anatomical adaptations for support (see figure). These include strong top-line ligaments, a robust rib cage, and the ability to stiffen the thoracolumbar region into a hydrostatic tube by maintaining abdominal muscle tone. By using these passive and semi-passive mechanisms, horses (and other large animals) are able to support their weight with respect to gravity, while maintaining the flexibility needed to move in the world and “make a living”.

Before accommodating a rider, a horse must be able to manage his own body competently. Horses stand for up to 23 hours each day, only lying down for brief periods of REM sleep. If they lay down for longer periods, their weight would crush their muscles and depress their respiration. Their unconscious postural control system enables them to have “standing sleep”, and maintains upright support, whether they’re sleeping, playing or doing a piaffe. After all, gravity never takes time off!

A four-legged table best supports weight right in the middle of its four supports. The horse, however, has a heavy head and neck protruding out from his front end, away from his four-legged supports. This shifts his center of mass (COM) forward. This means the best and most balanced weight-bearing area is just behind his withers. When a saddle rests behind the withers, it places the rider right above the horse’s center of mass. When all is perfect, the rider’s weight will increase the load of the horse’s own body weight in a predictable way that is easy to manage.

What is “center of mass”?

Have you ever tried to balance a pencil on your fingertip? Center of mass (COM) is the theoretical and actual center point of a physical entity. It is where the object’s entire mass acts as if it is a single point.

In living organisms, this spot is always changing as we move our limbs through our environment, but it doesn’t move very far. In humans, the center of mass is located between the navel and the small of the back when we stand with both feet on the ground. Your weight goes straight down, between your feet. If you stick out your leg, you can feel your body automatically adjust, so that your weight still has support under it. Your postural control system is so sensitive that every voluntary movement you make results in subtle postural adjustment to the COM. This is because your brain is avoiding unfortunate contact with the planet – i.e. a face plant!

Not all weights are created equal

What’s easier to carry – a sack of flour, a toddler having a tantrum, or your baby on your hip? The first is just a load. It will increase your muscle work but you are still carrying dead weight. The second – controlling a strong, determined and illogical creature, while doing your best to prevent harm to your load or yourself – is a nightmare. Carrying a baby (who wants to be carried) is another thing entirely. A baby cuddles close to your body (and may even hang on), and moves with you, not against you, so you can focus on other things. How can we translate this knowledge to the riding experience?

The best riding experiences happen when you and the horse move as one. This comes from perfect balance and communication. It is interesting to note that when humans and horses become a dyad (something that consists of two elements or parts), their spines form a right angle. The rider must keep her trunk balanced above her own COM, which in turn is balanced above the horse’s COM. What happens when you lean off to the side? Either you fall off, or the horse compensates for your balance change. This explains why some horses can show issues with an amateur rider that disappear when a professional gets on – there is a problem with the amateur they can’t compensate for.

It takes a long time to learn to ride skillfully because balance is very much a learned skill. A rider will never be like a sack of flour, because the rider has a dynamic nervous system that is continuously compensating for minute changes in her own balance. Even breathing requires active postural compensation! The “busier” a rider is, the more compensation is needed from both her and the horse. Horses are generous creatures. Most will work very hard to stay underneath their riders even though this distracts from their own athletic performance.

Connecting two minds and bodies

Beyond the biomechanics of horse and rider managing their individual and combined weight bearing, there is also a neurologic interaction between their conscious and unconscious nervous systems – and that’s where the magic lies! Both horse and rider possess a conscious intent, which hopefully aligns when a difficult task lies ahead.

Let’s take a very simple example – trotting along a straight line. The rider visualizes the intended path because the horse, with his eyes set on the sides of his head, does not have convergent vision. The rider can signal the desired speed and direction in a number of ways: voice, legs, hands and body. While some horses are trained to voice command, we can all agree that verbal instructions are the least reliable way to communicate with most horses. What other tools are more effective?

The importance of postural balance to biomechanics

Your postural balance is by far the best way to get a horse to pay attention, because human and equine nervous systems both make remaining upright, at all costs, a very high priority. But how often do riders give their horses conflicting information? If a beginner rider fears falling at the trot, for example, she may lean forward and grab the mane. Moving her weight forward is the clearest possible signal for the horse to increase speed. The horse is dynamically trying to keep the rider’s weight beneath his legs. Unfortunately, faster is exactly what the rider did not want!

Your hands on the reins can also convey erroneous communications through another neurologic mechanism. Did you know that the jaw joint (TMJ) is closely aligned with posture and movement? Try this: stand up straight, with your eyes ahead and hands down at your side. Now, stick your jaw out as far as you can. Did you feel how your upright posture shifted forward to match the jaw’s position? Now try backwards and side to side. This is an automatic mechanism, built into our nervous systems to keep the brain safe.

So if a rider is unconsciously pulling on one side, she will literally be turning the horse by shifting his balance towards his jaw. Similarly, if a rider tries using her legs to influence the horse, but cannot do so without changing her own balance, the horse will likely choose to respond to the most compelling information — the rider’s balance. Why? Because a rider’s balance can seriously impede a horse’s own support system; and most horses, in their generosity, try to protect the humans on their backs!

We can’t fight gravity. But, with skill and awareness, and a basic understanding of biomechanics, we can make the most of the beautiful interaction between horse and rider.