Bits are required by many disciplines. With so many types to choose from, how do you select the best option for your horse? Let’s look at bit action and its effect on the mouth.

Knowing how a horse’s mouth responds to a bit is crucial when it comes to making the best choices for your own equine. In the last issue, I described the findings of a radiographic study that looked at the position of four snaffle bits (jointed, Baucher, KK Ultra, and Myler Comfort) in the horse’s mouth. Now I’ll describe another facet of this study: the evaluation of movements of the horse’s jaw and tongue in response to a bit.

Bitting Behaviors

The radiographic suite at the College of Veterinary Medicine at Michigan State University is equipped to offer a technique called fluoroscopy. It allows X-rays to be recorded on videotape. This is a wonderful technique for observing what happens inside the horse’s mouth, where the movements of bit and tongue are usually invisible.

During our study, each horse wore a bridle that was adjusted so the bit created a small wrinkle in each corner of the lips – just enough to fit the bit snugly, but not so tight that the bit caused a “smile”. The flash noseband was adjusted flush against each horse’s face, but not tight enough to indent the skin, so it did not prevent the horses from moving their jaws or opening their mouths.

I have posted video clips of the behaviors I’m about to discuss on the McPhail Chair Website (cvm.msu.edu/dressage). However, you shouldn’t draw any conclusions about the bits chosen to show the various behaviors. These clips were selected because they clearly show specific behaviors, not because the behaviors were typical of a particular bit. We have performed research on a wide variety of bits, so some bits shown in the videos and in the still photographs that accompany this article may differ from those I discussed in my previous article.

Behavior #1: Mouth Quiet

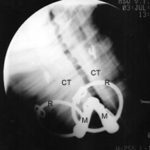

The horse’s mouths were quiet for the majority of time they were observed. We defined “quiet” as the mouths being closed, with the upper and lower cheek teeth in occlusal contact and the tongue showing minimal movement, so the bit did not move perceptibly within the oral cavity (Figure 1).

Behavior #2: Gentle chewing

When horses gently chewed, there was a little movement between the upper and lower teeth, but the lips weren`t parted. The tongue moved but remained under the bit, with the tip of the tongue located in the front part of the oral cavity close to the incisor teeth (Figure 2). This type of chewing motion occurs when the horse is relaxed and accepting the bit. This action introduces small bubbles of air into the saliva, causing it to become foamy.

Behavior #3: Opening the mouth

Horses would sometimes open and close their mouths repeatedly while keeping the tongue under the bit and the tip of the tongue close to the incisor teeth. This behavior produces a clacking noise as the upper and lower teeth meet when the mouth closes. Figure 3 shows the mouth being opened wider than when the horse chews the bit.

Behavior #4: Raising the bit

A horse can use his tongue to raise the bit closer to his cheek teeth. At times, he may actually grasp the bit between his upper and lower cheek teeth (Figure 4). On the video, the mouthpiece seems to catch between the teeth, then suddenly releases. Grasping the bit between the teeth was associated with the sound of enamel on metal. You will sometimes see evidence of this grasping action in the form of scratches on the mouthpiece.

Behavior #5: Drawing back the tongue

A horse’s tongue is very mobile and has a lot of freedom to slide back and forth under the mouthpiece of the bit. Horses sometimes withdraw their tongues, pulling the front part back towards the teeth. This retraction of the tip of the tongue under the mouthpiece is easily seen in the videos. The tongue can be withdrawn so far that it disappears entirely from the front part of the oral cavity (Figure 5), even without the horse opening his mouth. The muscles that retract the tongue attach to the hyoid bones, which are stabilized by muscles on the underside of the neck that run from the hyoid bones to the sternum. Not surprisingly, tongue retraction may be associated with tension in the muscles on the underside of the neck.

Behavior #6: Tongue over the bit

None of the horses in this study put his tongue all the way over the bit. On several occasions and in several horses, however, the body of the tongue bulged over the mouthpiece, forming a cushion between the mouthpiece and the palate (Figure 6). This behavior was observed quite frequently and may have been a way for the horses to protect their palates from painful bit pressure.

Swallowing While Bridled

There’s debate as to whether horses are able to swallow while bitted, and whether the type of bit used affects ease of swallowing.

In order to swallow, the horse must be able to move and retract his tongue. Researchers have questioned whether the presence of a bit interferes with tongue movements and prevents swallowing. In the McPhail study, we used an endoscope to record the movements of the larynx as the horses cantered on a treadmill while flexed at the poll. Analysis of the videotapes showed there was a lot of variation among the 12 horses studied in terms of how frequently they swallowed. However, this frequency was the same while the horses were wearing a jointed snaffle, a halter, or a bitless bridle, and was only slightly lower for the Myler snaffle. Therefore, we concluded that bits do not interfere with a horse’s ability to swallow.

Choosing a Suitable Bit

There is no simple way to select the “best” bit for an individual horse. But the results of our research have given us some insights into why horses may be uncomfortable or resist the action of a particular bit. When choosing a bit, consider the following factors:

1. Size: The width and thickness of the bit should fit the dimensions of the horse’s mouth. The width of the mouth is the distance between the corners of the lips. The corresponding bit- mouthpiece measurement is the distance between the insides of the rings or cheeks, and the mouthpiece should be up to ½” wider than the horse’s mouth to avoid the bit pinching the lips. Some horses appear to dislike jointed bits that are much wider than this because they hang too low on the tongue.

The thickness of the bit is the diameter of the mouthpiece, usually measured 1” from the rings, in the area where the mouthpiece crosses the bars of the horse’s mouth (the toothless spaces). Traditionally, a thicker bit was assumed to have a milder action than a thinner one, as the force is spread over a larger area and therefore produces less pressure. However, as I discussed in my previous article, our research suggests that many horses’ oral cavities are too small to accommodate thick bits, and that such horses are more comfortable with thinner mouthpieces.

The space between the upper and lower bars when the mouth is closed gives an indication of the maximal bit thickness a horse can accommodate. You can assess the size of this space by parting your horse’s lips and inserting a finger between his gums in the area where the bit lies. The size of his tongue is another limiting factor, as the bit must compress the tongue in order to fit into the oral cavity. A horse with a large tongue has more trouble making room for the bit, especially if his palate is flat and not arched. However, the tongue is very malleable and can assume many different shapes, as shown in the photos.

2.Type: Bitting is not a “one size fits all” proposition. Even after measuring the size and assessing the shape of a horse’s oral cavity, there is still an element of trial and error in finding the most comfortable and appropriate bit for an individual horse. The horses in our studies appeared most comfortable in bits that did not put pressure on the palate. Many horses went well in the KK Ultra. Some horses that were uncomfortable in conventional snaffles appeared more content in Myler Comfort bits; this may be due to the different mechanics associated with the swiveling action of the Myler mouthpiece.

Hilary Clayton, BVMS, PhD, Diplomate ACVSMR, MRCVS, is a world renowned expert on equine biomechanics and conditioning. Since 1997, she has held the Mary Anne McPhail Dressage Chair in Equine Sports Medicine at Michigan State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, East Lansing. The position focuses on dressage- and sport horse-focused research. This research was made possible by a grant from the U.S. Eventing Association. The research was performed by Dr. Jane Manfredi when she worked in the McPhail Center through the Merck-Merial Veterinary Scholars Program. Reprinted with permission from the USDF Connection.