Oral cancers can be aggressive and challenging to treat, but an Integrative approach to animal oral cancer treatment that incorporates alternative therapies can extend longevity and improve quality of life.

Cancer is not an outside enemy that invades the body. It is the patient’s own cells going rogue because the conditions (terrain) have become inhospitable. This article focuses on oral cancers in dogs and cats and an integrative approach to animal oral cancer treatment. This article will make you learn how an integrative approach to animal oral cancer treatment can enhance a patient’s quality of life and give them more time with their owners.

All cancers result from a combination of four conditions

- Deficiencies of essential nutrients the body needs to function properly. These include vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, and amino acids.

- Toxicities to a level that overwhelm the body’s organs of elimination, resulting in “dis-ease”.

- Mitochondrial dysfunction, resulting in inadequate energy production (ATP) and inhibited communication with the microbiome.

- Trapped emotions, which have been shown to be associated with all dis-ease. The tumor type, its location in the pet’s body, and the owner’s emotional state all have significance. Oral tumors may be associated with owners that are closed-minded and find it hard to receive new ideas or express their needs and desires.1

In most cases, a combination of deficiencies and toxicities play a part in cancer development, and integrative approach to animal oral cancer treatment can be a successful strategy.

Oral cancer in pets, especially dogs, is common

Statistics in dogs:

- Oral tumors make up 6% to 15% of all tumors in dogs.

- Melanomas are the most common, accounting for up to 30% of cases.

- Melanomas are highly aggressive tumors with a strong likelihood of early metastasis (primarily to lymph nodes and lungs) in 50% to 80% of cases.

- Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is another frequent neoplasm, representing 25% of oral tumors. SCC is also known for its aggressive local invasion.

- Fibrosarcomas in dogs are somewhat less common than melanomas and SCC but are still significant. They are locally aggressive and often affect older dogs. Oral fibrosarcomas account for up to 8% to 10% of all oral tumors. They are typically locally aggressive and often infiltrate surrounding tissues and bone, making complete surgical removal challenging. They have a high tendency to recur locally even after surgery. Certain large breeds, like Golden Retrievers, are more predisposed.

Statistics in cats:

- Oral tumors account for 3% to 10% of all tumors.

- Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common, making up 70% of cases. It is extremely aggressive with the potential to cause significant destruction to nearby tissues, including bone.

- Fibrosarcomas in cats, though less common than SCC, are the second most frequent type. As in dogs, feline fibrosarcomas are aggressive but tend to metastasize later than other types. They commonly affect middle-aged to older cats. Fibrosarcomas are sometimes associated with injection sites, especially vaccines, making this a unique risk factor for feline cases.

Other types of oral tumors in pets:

- Acanthomatous ameloblastoma (previously called acanthomatous epulis): A benign but locally invasive tumor arising from the periodontal ligament. It typically affects the gums, particularly in a dog’s lower jaw. Although benign, it can invade the bone and cause significant oral discomfort, requiring surgical removal.

- Peripheral odontogenic ribroma: Another benign tumor formerly categorized under “epulis,” arising from periodontal tissues. It grows slowly and is less invasive than acanthomatous ameloblastoma. This tumor generally affects the gums and is more common in older dogs.

- Osteosarcoma of the jaw: Though osteosarcoma commonly occurs in limbs, it can also affect the bones in the jaw. Oral osteosarcoma in pets is particularly aggressive and can invade local structures, with a risk of metastasis to the lungs and other organs.

- Chondrosarcoma: A rare type of cancer that arises from cartilage cells and can occur in the jaw or other areas of the skull. It tends to be less aggressive than osteosarcoma but can still invade nearby tissues and cause discomfort.

- Undifferentiated sarcomas: These less common, aggressive soft tissue tumors can originate in various oral tissues. They are challenging to classify under standard types and may have varied behaviors depending on their location and growth patterns.

- Papillomas: Usually benign growths caused by papillomavirus. They appear as small, wart-like lumps in the mouth, often in young dogs. Although not malignant, they may cause irritation or lead to infection.

Early cancer detection is crucial, as the five-year survival rate for pets with untreated oral cancers is less than 20%. With an integrative approach to animal oral cancer treatment, however, survival rates and quality of life can improve dramatically.2

Western approach to diagnosing and treating oral tumors

Diagnosis typically involves:

- A thorough physical exam

- Preoperative blood work (CBC, chemistries, thyroid and UA)

- A fine-needle aspirate or biopsy of the mass

- Imaging (X-rays, CT, or MRI) may be warranted to evaluate the extent of bone involvement and dissemination of the mass.

Surgical resection is the primary treatment for many oral tumors in pets and aims to remove as much of the tumor as possible with clear margins. In some cases, this involves a mandibulectomy or maxillectomy (removal of part of the jaw). While somewhat effective, this can lead to disfigurement, pain, and reduced quality of life, deterring many pet owners from pursuing it.2

For pets diagnosed with melanoma, fibrosarcoma, or squamous cell carcinoma, survival outcomes vary depending on the type of tumor and the treatments used:

- Melanoma: Surgery is the primary approach for controlling local melanoma tumors in Western medicine, with dogs often achieving one to two years of survival if complete resection is possible. However, due to melanoma’s high potential for spreading, chemotherapy and radiation may add limited survival benefits, generally extending life by six to 12 months post-treatment.3

- Fibrosarcoma: In Western medicine, surgical removal is also standard for fibrosarcomas. If wide margins are obtained, survival may extend to one to two years, but local recurrence is frequent. Radiation therapy can be used if surgical margins are insufficient. Chemotherapy generally has limited impact on survival for fibrosarcoma’s, unless there is a high risk of metastasis.3

- Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC): Outcomes depend heavily on the cancer’s location. In oral SCC, early surgical intervention can lead to survival of one to two years, with radiation providing additional control if resection is not complete. Chemotherapy may be used to address metastatic concerns, but its effect on survival varies.3

When surgery does not completely clear the tumor, or if it is inoperable, radiation therapy may be used, though it has side effects such as tissue damage in surrounding areas. Chemotherapy is another option, especially for aggressive melanomas, but is often not curative.2

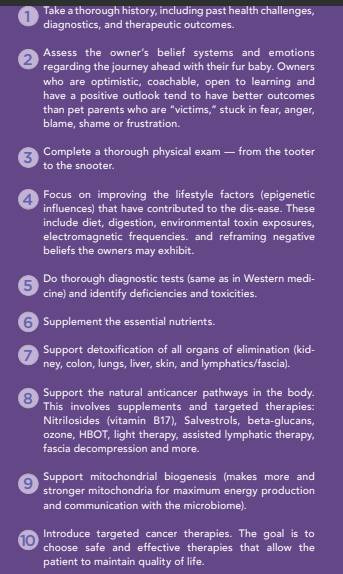

A bioregulatory approach to oral cancer in dogs and cats

In an Integrative approach to animal oral cancer treatment bioregulatory approach is also important. This approach tests for everything a Western practice does, but also seeks to identify and resolve the root cause(s):

- Cancer markers: Thymidine Kinase 1 (TK1) is involved in cellular proliferation through the recovery of Thymidine in the DNA salvage pathway. TK1 is a good marker for identifying growth in certain cancers, as it is elevated in actively dividing tumors. It is also a useful marker for monitoring therapeutic efficacy. As the tumor burden goes down, so does TK1.

- Systemic inflammation: Canine C Reactive Protein (cCRP) measures inflammation.

- Nutrient deficiencies: Vitamin D and magnesium play a vital role in the innate immune system. University studies have shown that 85% of animals eating a kibble diet are vitamin D deficient. Having done nutrient testing on thousands of animals over the last five years, I found that almost 90% of tested animals eating a kibble diet had multiple significant deficiencies in nutrients, including zinc, selenium, calcium, copper, vitamin D, magnesium and B vitamins.

- Toxicities: Over 85% of the animals I tested for heavy metals (arsenic, mercury, lead, cadmium, strontium, and antimony) had significant elevations in four or more heavy metals.

- Glyphosate: This chemical is toxic even at low levels, melting the actin filaments in the tight junctions and inhibiting mineral absorption. Every animal I have tested has been positive for some level of glyphosate.

- Testing for mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressors is a new concept in veterinary medicine. Canine tumors share mutational hotspots with human tumors in oncogenes, including PIK3CA, KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, KIT and EGFR. Companies then study what chemotherapeutic drug is most effective against the gene mutation, guiding the treatment options with more precision. The downside of this technology is that, at this time, only chemo drugs are being studied for efficacy against various gene mutations. I trust that in the future, biomarkers will be found that allow testing on safe and effective alternative therapies as well.

The expanded cancer treatment toolkit

The traditional “toolkit” (surgery, chemo and radiation) are insufficient to meet the challenges of today’s turbo cancers. Following are some other safe and effective options in an integrative approach to animal oral cancer treatment:

- Ozone therapy: Thousands of published articles cite the use of ozone in cancer therapy. Ozone therapy turns on over 200 anti-inflammatory pathways, can improve oxygenation, and stimulate the immune response. Improved cellular oxygen levels result in an environment less favorable for tumor growth. Common methods of administration include intravenous (MAHT), intramuscular (mAHT), intralesional, subcutaneous and rectal.

- Photodynamic therapy (PDT): PDT uses a photosensitizer (like curcumin, riboflavin, indocyanine green or vitamin C, to name a few) that is taken up by the abnormal cells. When the specific wavelength of light that activates the compound is introduced, it makes the compounds more enzymatically active. This results in free radicals that induce cancer cell death. Research has shown that PDT can also stimulate immune cells such as neutrophils and macrophages, potentially boosting the body’s natural defenses against cancer. This immune-stimulating effect makes PDT appealing in integrative cancer care.5

- Methylene blue: Systemic use in cats is limited. Traditionally used to treat methemoglobin, methylene blue can cause toxic effects including haemoconcentration, hypothermia, acidosis, hypercapnia, hypoxia, increases in blood pressure, changes in respiratory frequency and amplitude, corneal injury, conjunctival damage, and Heinz body formation. However, it can be used topically in dogs and sparingly in cats with oral tumors due to its photodynamic activity. Methylene blue is activated by specific wavelengths of light, which produces reactive oxygen species that can selectively destroy cancer cells. It also activates the fourth activation center in the Krebs cycle, improving mitochondrial activity. Using methylene blue topically is being increasingly explored in oncology for its lower toxicity, making it useful for delicate areas like the oral cavity, where many traditional therapies pose higher risks.4

- Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT): When used in conjunction with antiangiogenic supplements, HBOT improves oxygen concentration levels, making the environment less favorable for cancer tissue to grow.

- Supplements: Those that target anticancer pathways are effective adjunct therapies. They include Nitrilosides like B17, Salvestrols (natural phytochemicals produced within plants — these are metabolized by the CYP1B1 enzyme which then produces anti-cancer metabolites), mushrooms, CBD, low dose Naltrexone, and mistletoe.

- Immune modulation: Therapies that stimulate the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells are increasingly used in veterinary oncology. By enhancing the immune system’s detection of cancer, immune modulators can help slow disease progression, particularly in combination with other treatments that target tumor cells directly.

- Targeted gene therapy: This approach aims to correct or modify genetic mutations that drive cancer growth. Targeted gene therapy has shown potential in reducing tumor growth by delivering therapeutic genes directly to cancer cells, leaving normal cells less affected. This specificity minimizes the adverse effects seen with broader treatments like chemotherapy and radiation.

- Checkpoint inhibitors: These drugs block proteins that tumors use to evade immune detection, helping T-cells attack cancer cells. They are being explored in veterinary medicine, showing promising results in dogs, particularly for melanoma.

- Immunotherapy: This approach utilizes the body’s immune system through various modalities, including monoclonal antibodies, cancer vaccines, and cytokine therapy. It is often less toxic than traditional chemotherapy and has demonstrated effectiveness in treating various cancers.

- Targeted biological pathways: Focusing on specific molecular pathways and mutations in cancer cells allows for personalized treatments, with combination therapies enhancing effectiveness.

Too often, veterinarians are forced to tell their clients: “There is nothing more that can be done.” We hear “cancer” and think “no hope”. But there is more that can be done such as an integrative approach to animal oral cancer treatment. Treating cancer requires a multifaceted approach. We need to have a bigger toolkit and strategies that bring together body, mind and spirit.

By focusing on restoring the body’s terrain, utilizing nature’s pharmacy, and integrating cutting-edge therapies, it is possible to not only extend the lifespan but also improve quality of life for pets and their owners. This integrative approach to animal oral cancer treatment provides the balance necessary to help the body move from surviving to thriving.

____________________________________________________________

1Louise Hay. Available at: https://www.louisehay.com/.

2American College of Veterinary Surgeons (ACVS). “Oral Tumors.” Available at: https://www.acvs.org/small-animal/oral-tumors/.

3https://www.nahf.org/article/canine-mouth-cancer-life-expectancy.

4Frontiers in Veterinary Science. “Oral Tumors in Dogs and Cats.” Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/veterinary-science/articles/10.3389/fvets.2024.1359426/full.

5Today’s Veterinary Practice. “Introduction to Oral Neoplasia in the Dog and Cat.” Available at: https://todaysveterinarypractice.com/dentistry/practical-dentistry-introduction-to-oral-neoplasia-in-the-dog-cat/.

6National Institutes of Health. “PMC11092801 – Oral Tumors in Veterinary Medicine.” Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11092801/pdf/nihpp-rs4289451v1.pdf.

American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA)

https://www.merck-animal-health-usa.com/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30223456/

Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/veterinary-science/articles/10.3389/fvets.2022.803093/full

American College of Veterinary Surgeons. https://www.acvs.org/

Frontiers in Immunology. “Immunological Mechanisms in Cancer Therapy.” Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1335920/full.

VCA Hospitals. “Fibrosarcoma and Feline Sarcoid.” Available at: https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/fibrosarcoma-and-feline-sarcoid.

VCA Hospitals. “Post-Vaccination Sarcoma in Cats.” Available at: https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/post-vaccination-sarcoma-in-cats.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2023.1264961/full

https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/12/23/12276

ResearchGate. “Methylene Blue in Photodynamic Therapy.” Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230888444_Methylene_blue_in_photodynamic_therapy_From_basic_mechanisms_to_clinical_applications.

MDPI. “Photodynamic Therapy and Cancer.” Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/25/2/1023.

Schubert K, Steinhauser I. “The Role of the Microbiome in Cancer Therapy.” Frontiers in Microbiology, 11, 294. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.00294.

Feng Q, Zhang C, Zhao X. “The Role of the Gut Microbiome in Cancer.” Nature Reviews Cancer, 19(12), 794-810. doi:10.1038/s41571-019-0214-3.

Turnbaugh PJ, et al. “The Human Microbiome Project.” Nature, 449(7164), 804-810. doi:10.1038/nature06244.

Gonzalez MJ, Seymour R. “Dietary Influences on Epigenetic Changes in Cancer: Implications for Cancer Prevention and Treatment.” Nutrition Reviews, 79(7), 724-734. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuaa077.

Zeller, G., et al. “Potential of Fecal Microbiota for Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer.” Nature Medicine, 20(3), 303-308. doi:10.1038/nm.3494.

Gosalbes, M. J., et al. “Microbiome: A Key Player in the Field of Human Health.” Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease, 22(1), 1-10. doi:10.3402/mehd.v22i0.5896.

“Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Cancer: Emerging Insights.” Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 9, 123. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.689488.

Frontiers in Oncology. “Cancer and Immunology: Emerging Perspectives.” Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2021.738323/full.

Today’s Veterinary Practice. “Introduction to Oral Neoplasia in the Dog and Cat.” Available at: https://todaysveterinarypractice.com/dentistry/practical-dentistry-introduction-to-oral-neoplasia-in-the-dog-cat/.

Virginia Veterinary Specialists. “Oral Tumors in Dogs and Cats.” Available at: https://vavetspecialists.com/oral-tumors-in-dogs-and-cats/.