This serious disease is increasing in incidence, yet is still relatively rare in most regions. Find out what causes leptospirosis, how it’s treated, and whether or not you should consider vaccination.

If you’ve heard of leptospirosis, you may know that the number of cases has been increasing recently across both the United States and Canada. As a result, dog caregivers are asking if they should have their canine companions vaccinated against the disease. Let’s look at what causes leptospirosis, as well as its symptoms, treatment and prevention, and whether or not you should consider vaccination.

What is leptospirosis and how does it spread?

Leptospirosis is a zoonotic disease, which means it can spread from animals to people. It’s caused by a Leptospira bacterial infection. Although there are over 200 strains of this organism found worldwide in soil and water, most do not cause clinical illness. Thus far, approximately seven leptospirosis strains (serovars) are considered clinically important for dogs.

Leptospirosis is spread through the skin or mucous membranes via contact with infected tissue, urine, blood or other bodily fluids, except saliva. Most commonly, dogs acquire the disease by closely sniffing or walking through urine-contaminated water, soil or food. They can also get it from contaminated bedding, a bite from an infected animal, or by eating infected tissues or carcasses. Very rarely, dogs contract leptospirosis through breeding, or from the organism breaking through the placental wall from the infected dam to her puppies. Raccoons, skunks, foxes, moles, squirrels, opossums and rats are considered common carriers and can excrete the bacteria periodically or even continuously for several years. Leptospirosis is rare in cats.

The disease is found most commonly in areas with warm climates and high annual rainfall. Fast-flowing or large bodies of water are not usually of concern, but contaminated standing puddles and wet mud from high rainfall or flooding could be an issue. Dogs may also be exposed to leptospirosis when travelling through rural areas populated with infected wildlife, farm animals and rodents. Climate change and residential development in formerly rural areas open up another exposure source.

As leptospirosis is a zoonotic disease, those in contact with an infected dog should wear rubber gloves, clean up urine, and not let the dog lick their faces until treatment is completed. Try to encourage the infected dog to urinate away from standing water and where people or other animals congregate. Wash your hands with warm soapy water each time you come into contacted with an infected dog.

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms are many and varied, and can be mistaken for other health problems. If your dog shows any of the following signs, take him to the vet as soon as possible for a check-up, tests and diagnosis.

- Fever

- Shivering

- Muscle tenderness

- Reluctance to move

- Lethargy

- Increased thirst

- Changes in the frequency or amount of urination

- Dehydration

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Loss of appetite

- Jaundice (yellow coloring of the skin and mucus membranes)

- Inflammation within the eyes

Prompt treatment is paramount. If caught too late, leptospirosis can result in kidney failure, with or without liver failure. Less commonly, dogs may develop severe lung disease and difficulty breathing, swollen limbs from the accumulation of edema, or excessive bleeding (blood in vomit, urine, stool and saliva), nosebleeds and pin-point hemorrhages in the skin or mucus membranes (called petechiae).

How is it diagnosed and treated?

The most common diagnostic tool for leptospirosis is the Microscopic Agglutination Test (MAT). This titer test measures the serum antibody increase against Leptospira spp. Serum titers of at least 1:1600 or higher, and an 8- to 16-fold rise in titer three to four weeks later, is typically expected to confirm the disease, but false positive results are quite common. A newer more definitive and accurate diagnostic test is the DNA-PCR, which detects the DNA of the actual Leptospira spp in whole blood or urine.

Treatment requires conventional medication. If caught early enough, leptospirosis is rapidly and effectively treated with antibiotics such as penicillin, doxycycline, ampicillin and amoxicillin. Late diagnosis may require emergency care, and some residual kidney or liver damage may result.

While the dog is being treated, be sure to support his immunity with a healthy lifestyle. Homeopathic remedies such as Aconitum napellus, Arsenicum album and Mercurius corrosivus can also be helpful, but it’s important to work with a homeopathic veterinarian to ensure the correct remedies and dosages are used.

Should my dog be vaccinated against leptospirosis?

Should my dog be vaccinated against leptospirosis?

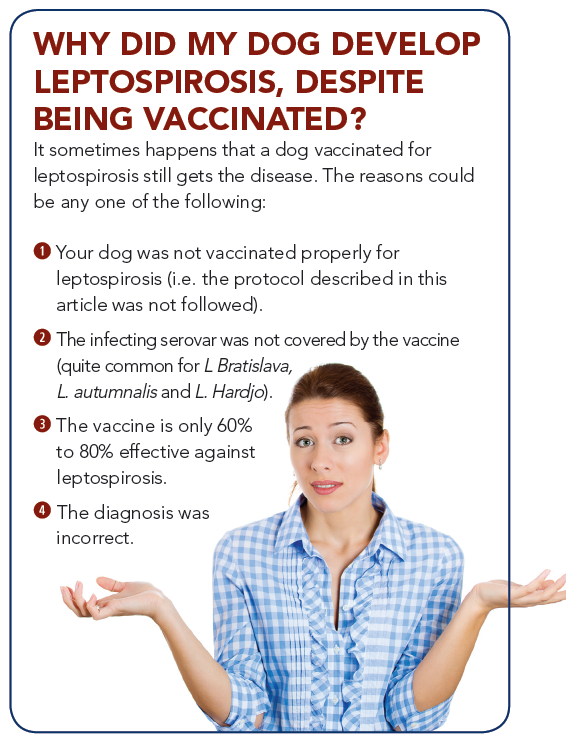

A vaccine is available for leptospirosis but it only covers four of the seven clinically significant serovars: namely L. canicola, L. icterohaemorrhagiae, L. grippotyphosa and L. pomona. The vaccination protocol is an initial shot and a booster three weeks later. After that, the vaccine is given annually to maintain efficacy. If the annual booster lapses, the dog should start the protocol again from the beginning.

However, please keep in mind that the leptospirosis vaccine is most commonly associated with acute and per-acute adverse reactions. Also keep in mind that true confirmed clinical cases of leptospirosis are still rare. This means you need to weigh the disease exposure risk in your area against the adverse vaccine reaction risk before making a decision to vaccinate your dog. As well, the leptospirosis vaccine won’t guarantee that your dog won’t get the disease anyhow (see sidebar at right).

Although leptospirosis is a serious disease, and its incidence it increasing, it’s important not to panic. Do some research into whether leptospirosis is an issue in your area – your veterinarian, doctor and public health office can help. Consider the risks carefully before vaccinating, and in the meantime, give your dog a healthy lifestyle to help keep his immune system strong, and have him checked over by your vet if he shows any signs of illness.